Stranded Snowbikers Rescued After Getting Stuck in Ravine

What started out as a fairly routine backcountry freeride on snowbikes — dirt bikes with ski and track conversions designed for deep snow — turned into an unexpected situation that left Craig Hunter and three other party members stranded in a deep ravine in freezing temperatures. In his own words, Hunter shared with Garmin the details of their 40-hour ordeal, SOS, night in the woods and rescue in the Canadian Chic Chocs. Plus, the snowmobile dealer shared what he learned from the trying experience.

“A few members of our group dropped over a ridge into a section of steep trees that should have been easily rideable if the snow was different. However, that day, the snow was super powdery, bottomless and filled with buried pine trees. These trees hold pockets of air under their branches when buried in snow, so when you ride near them or over them, the bikes sink immediately — sometimes 6’ to 8’.

One of my party members had ridden this mountain before, but it was later in the season when the snow was more set up, and therefore provided more floatation and traction. The trees had also been packed more tightly then, so the invisible air pockets and tree holes were not a concern. This time, he got stuck.

I had followed him into the steep, treed slope to help him get unstuck, but it became obvious that turning around and going upwards and out the way we came in would not be possible. He believed there was a trail along the top of the mountain that gradually sloped down, so if we continued horizontally across the mountain, we would intersect the trail and ride out.

So the four of us continued along the very steep slope, occasionally encountering deep tree holes that would completely swallow the bikes. The tree line was dense at the top, so riding through it wasn’t possible, and it gradually forced us downhill into a river bed. There, we decided to head for a ‘trail’ we saw on the GPS that would hopefully lead us to an old access road and out.

We battled the creek bottom, open water, tons of sticks, trees, dead ends and more — well past dark. At one point we found some snowmobile tracks in the ravine and followed them in circles for over an hour, but could not locate a route in or out of the ravine. It was snowing hard at this point, and the tracks eventually disappeared. When we ventured off the side of the river, the brush and trees were too dense to make much progress, so we kept getting forced back onto the partially snow-covered river.

The sides of the ravine were too steep, deep and dense to get out. The way we came in was not an option, and the way we were heading dead ended everywhere we looked. Progress was slow and exhausting, and we had been riding, digging, cutting branches and lifting the bikes for over 12 hours at this point. Two of us had bright, battery-powered helmet lights, but the other two had no lights. Eventually one party member began to have cramping and abdominal pain.

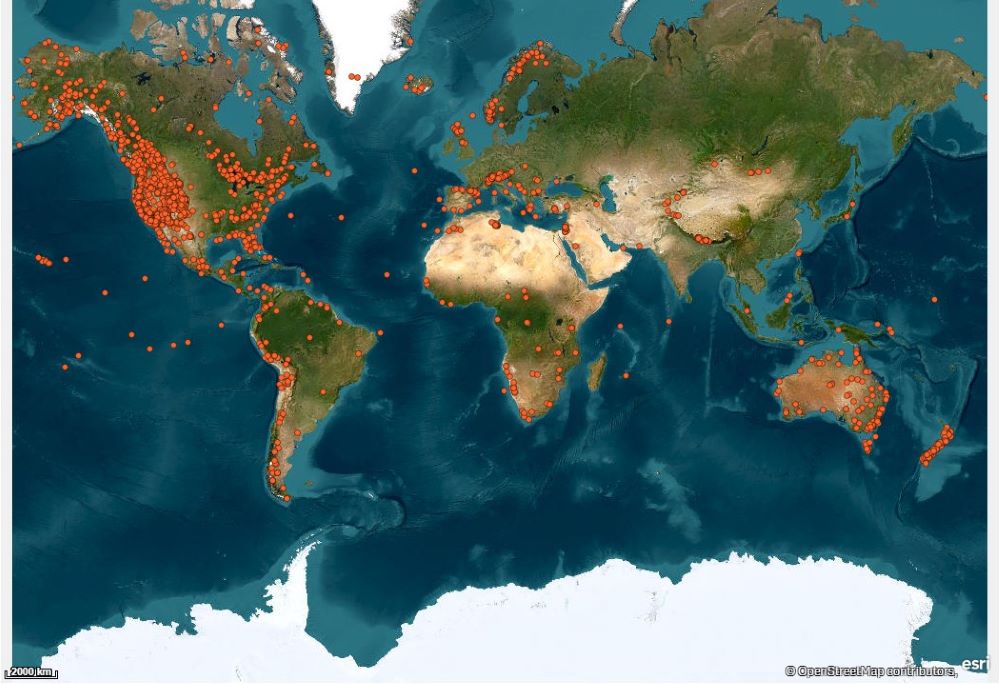

The river banks were getting steeper, the lines we were forced to take were getting riskier, and chances that one of us would make a mistake and end up in the water were getting higher. All four of us are very experienced backcountry motorcycle and snowmobile riders who have ridden all over the United States and Canadian mountains, but it became clear that we weren’t going to be able to ride out of this situation — at least not in the dark after a strenuous day of riding and digging.

Eventually — wet, exhausted and almost out of gas — we decided to set up camp and try again in the morning. It was 0 degrees and still snowing.

We stopped next to a large downed tree whose end was suspended about 4’ off the ground. We dug down to the ground under the tree to make a base for the fire so it would not melt down into the snow. Using birch bark for tinder and a lighter, we started a fire. To keep the fire going over the next 24 hours, we never stopped cutting wood with my Corona folding limb. We used a shovel to cut blocks of snow to build up walls and used some 4” round trees to provide support for a pine bough roof. A 10” x 5’ long log was our seat for the night — until we had to burn it.

While preparing the camp, I heard my inReach Mini satellite communicator chime. I had reluctantly — and at the request of my wife — gotten the device just a few weeks before. I almost didn’t get one because many of the places we ride in the western mountains have cellphone service, and a few of my riding buddies already have an inReach device. However those buddies were not on this trip.

The chime was a message was from my wife who hadn’t heard from us and wasn’t able to reach me on my cellphone. I used the device to inform her that we were OK, but would be spending the night in the woods. The primary task at the time was ensuring that we had a stable fire and shelter before the batteries in our lights ran out, so I didn’t communicate further until later that night. I was able to send my location, which was reassuring to both us and our families at home.

My wife had alerted local police who activated a search and rescue team. A local snowmobile guide service provided them with a BCA radio tuned to our channel. They were able to get close enough to make radio contact, but informed us that they were not going to be able to reach us at that time. They confirmed that we had fire and assured us that they would make another attempt at a later time. We collectively agreed that it was not a good idea for them to attempt to follow our route at night due to the hazards involved.

That night was very cold, and our base layers were wet from all the activity throughout the day and night. Although we were wearing high-quality, moisture-wicking base layers and breathable outer gear, the wet inner layers took a long time to dry out. Wet fabric on the skin exaggerates the cold. Since our riding style is very active, our gear is uninsulated, and most of us were only wearing a thin base layer. We took turns rotating around the fire to warm up, while also gathering wood and tending the fire. Although the fire was strong, feeding it was a full-time job, and it couldn’t be left unattended for more than a few minutes.

It was an excruciatingly long, cold and boring night. One of the guys kept falling asleep, presumably due to exhaustion and the beginning stages of hypothermia. We kept waking him up and forcing him to move around, as sleeping against the cold walls and floor of our shelter would only make his condition worse.

When morning finally came, and we attempted to start our bikes to leave, only two out of the four started. Although we had started them a few times throughout the night, the engines were encased in ice and the batteries were weak. One bike had a frozen throttle cable, but we were able to thaw it out. My bike cranked very slowly but wouldn’t fire. After multiple jump starts using one of the other batteries, we were in jeopardy of killing the second battery.

We realized that the bike was not going to start without a fresh battery, heat and other supplies. It was at this time, around 9 a.m., that we decided to trigger an SOS on the inReach. Since the other three party members could ride, I was limited to the hope that I could walk out in the trenches left by the snowbikes. I was not very optimistic about that, and we were out of options. Two of my party members took off to see if they could find the trail we had been looking for the night before.

I was preparing for a long, fairly hopeless walk when I heard the inReach chime. I found a message from one of our friends in town saying to stay put because a helicopter would be coming. There also was a local search and rescue team on foot attempting to reach us. I was unable to communicate with the other two bikes to tell them to come back, so we were now two separate groups.

The search and rescue team was using snowshoes and was only able to make about 100 meters of progress per hour. We were over a mile from their closest snowmobile access. Plus, due to the snowstorm, the helicopter kept getting delayed.

The inReach allowed us to get updates from both the staff at the GEOS International Emergency Response Coordination Center and our friends and family. This significantly reduced the amount of stress involved and assured us that we would eventually be found. It was just a matter of how long it would take and how we would get out. Without this technology, the situation would have been much worse. I was also able to instruct the search and rescue team where the other two riders could most likely be found, since they hadn’t made it to the trail by nightfall.

Although the search and rescue team never made it to our camp, they were eventually able to find the other two party members, who had made it about halfway to the trail before becoming too exhausted to continue.

Finally, around 9 p.m. — over 36 hours after we had originally left the truck — the sound of the helicopter broke the silence. After an intense and impressive extraction, the chopper dropped me and my other party member at a local airport. They were then able to go back to get the other two party members, who were with the search and rescue team.

A few mistakes were made that got us into this situation in the first place, but dozens of good choices followed which allowed us to survive the night, the next day and half of the following night until we could be retrieved. Search and rescue had attempted to reach us by snowmobile and snowshoes for 12 plus hours and were unable to get to us, given the conditions.

Although we felt ‘prepared enough’, lots of lessons were still learned from this experience:

- It goes without saying that you absolutely need to be able to start and maintain a fire if you expect to spend any amount of time in the woods in the winter. As a result, the most valuable asset we had was my saw. I have been carrying this saw since I started riding the backcountry in 2008, and it was in use almost 100 percent of the time. Fires in the snow take a surprising amount of wood to make heat. The wood is almost guaranteed to be wet and/or green. In our case the snow was too deep for us to walk very far, so we had to use what was close by. If you don’t have a saw, or a good saw, you may not be able to obtain enough wood to maintain a fire.

- Sending messages and our coordinates through text on the inReach device took the guesswork out of locating us for search and rescue, and it allowed us to communicate to our families that we were OK and more. We all felt terrible about the worry and chaos that this situation caused our families, but it would have been much worse for them if no one knew where we were, and whether or not we were alive, injured or lost. Just remember to conserve your phone battery if you’re going to be out for an extended period of time, and pair the device to your cellphone before you head into the backcountry. When you can text in a normal manner via a cellphone using the Earthmate app, instead of one letter at a time on the device, you can eliminate some confusion while communicating. I had just gotten the inReach for Christmas and almost didn’t take it. Without it, in a lost or stuck situation, your hopes for rescue are limited to radio contact or expecting someone to stumble upon your location.

- Space limits what we can carry every day, but we all wished we had a spare, dry layer to change into at night. Since we were only expecting to play close by in familiar areas, we hadn’t packed heavily like we would have for a longer or riskier trip. We were wet from perspiration from riding, digging and working, and even the best base layers take a long time to dry when it’s 0 degrees. Despite good gear and a solid fire, we froze all night. I was sorer from shivering and being tense all night than I’ve ever been from exercise or activity. Breathability of your outer shell is what allows your inner layers to dry out. Any gear can be waterproof, but if it doesn’t breathe, your inner layers will stay wet. Cotton especially is not a good option, as it gets wet, stays wet and doesn’t offer much insulation.

- Almost all of our communication equipment relies on batteries. Charge everything every night. Keep important small devices close to your body to keep them warm because the cold drains batteries even if they aren’t being used. The equipment is only worth having if you can turn it on and use it, and chances are if you need it for an emergency, it is going to be needed for an extended period of time. If you are in a bad enough situation to need search and rescue, do not expect them to come right away — there is no magic wand. Every situation is different, but be prepared for a long wait. Carry a small recharging battery with the correct cables to charge your communication devices.

- Always think rationally. Make only careful, methodical movements to make forward progress and avoid mistakes. Choose your riding (or your activity of choice) partners carefully. You are only as capable as your weakest link. If the weakest link has health issues, loses mental soundness, needs medication, etc., it could jeopardize everyone else in the group and be the difference between making it out or not. Stay calm because panic will never help anything and is usually dangerous. Things like fatigue, hypothermia, hunger and sleep deprivation make it difficult enough to think clearly, so panicking can really deteriorate a situation quickly.”

NOTICE: To access the Iridium satellite network for live tracking and messaging, including SOS capabilities, an active satellite subscription is required. Some jurisdictions regulate or prohibit the use of satellite communications devices. It is the responsibility of the user to know and follow all applicable laws in the jurisdictions where the device is intended to be used.