Jeep Trip From Vancouver Island to Arctic Ocean Proves Unpredictable

In early March 2020, Dave and Cheryl Byng, their son, Max, and Lab, Ranger, set off on an adventure in their winter-equipped, expedition-ready Jeep. It was meant to be a productive, grand journey from Vancouver Island to the Arctic Ocean. While Dave, a Fellow for the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, The Explorers Club and Royal Geographical Society as well as an expedition leader for Operation Wallacea, had plenty of experience traveling in rural areas worldwide, this trip turned out a little different. In his own words, Dave shared with Garmin the details of that trip.

“The expedition-equipped Jeep, readied for an 8,000-kilometer journey to the Arctic Ocean in the late Canadian winter, sat impatiently in the suburban driveway, looking oddly out of place surrounded by green grass and daffodils. A wide variety of modifications had recently been undertaken to prepare it for the extreme winter conditions anticipated along the route. A key piece of kit was the satellite navigation and communications system from Garmin — the inReach®. The route to the Arctic would traverse vast tracts of remote wilderness with few services, traveling in unpredictable winter weather and in often-challenging driving conditions. The combination of Garmin’s Overlander®, an all-terrain navigator, paired with the inReach Mini compact GPS and satellite communicator, was the perfect setup for the trip.

In the cool, predawn hours of Tuesday, March 10, we stuffed the last of our gear in the Jeep and left our Vancouver Island home to catch the first ferry of the day to the British Columbia mainland. While we weren’t heading to the tropics where I usually lead scientific expeditions, we were no strangers to winter driving, having spent most of our lives in rural and remote locations throughout the province. We knew an early start was essential to safely knock off the 900-kilometer leg planned that day as we navigated north through the deep freeze of the Interior Plateau.

The purpose of our trip was twofold. First, to continue our work with the Nisga’a people, located in a remote region of northwestern British Columbia, documenting their traditional food fishery of the eulachon, an oil-rich species of pacific smelt that spawns upstream of the mouth of the Nass River. Second, to head north to the Yukon and Northwest Territories, arriving at the Inuit hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk by March 19, to celebrate the spring equinox on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Along the way we planned to meet with groups of conservation-minded local youth, connecting them with programs and expeditions being undertaken by national and global conservation organizations such as the Canadian Wildlife Federation, Ocean Wise and Operation Wallacea.

Three days and 2,000 kilometers later, we arrived at Walter’s Camp, surrounded by the deep, heavy snow of late winter and perched on the eroding, muddy riverbank of the Nass River in Fishery Bay near the village of Gingolx. Eulachan are a highly prized, oil-rich fish — the first to arrive in the river toward the end of a long winter, when food is often scarce.

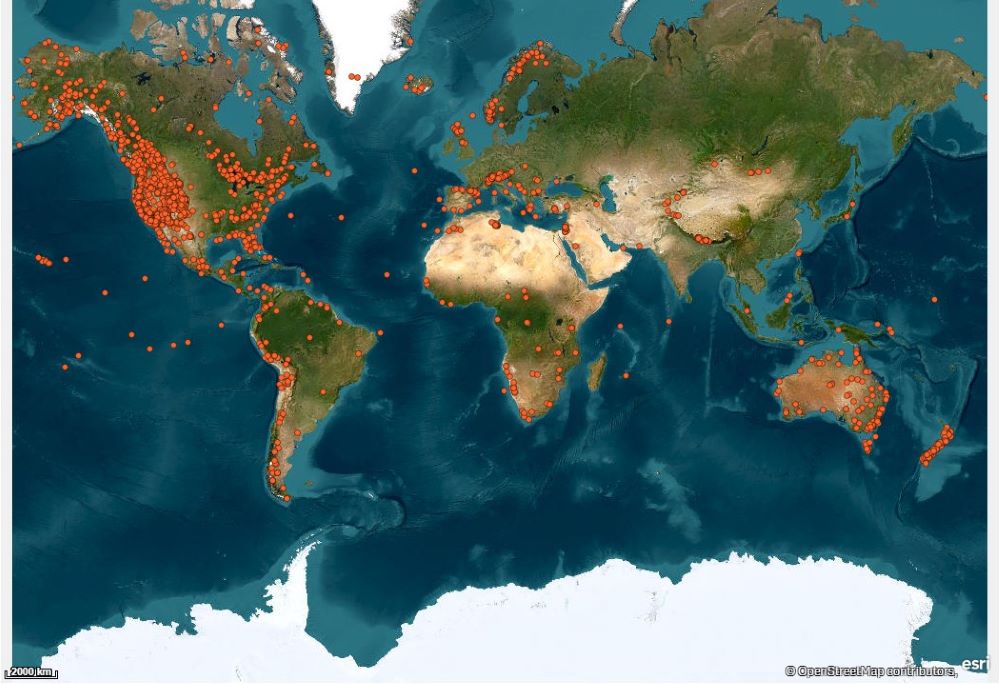

The fishery involves either setting nets through the ice-capped river, which is constantly cracking and heaving due to the nearby ocean’s tidal influence, or in open-water setting nets from small boats according to the rhythm of the tides. The weather can be brutal, with high winter winds blowing down the river to meet the inbound tide flowing up river’s wide mouth, creating ugly standing waves and freezing spray. Not much fun during the day and a lot less at night as you navigate the waves, dodging ice flows and trees drifting downstream while you work the nets. In addition to being utilized for navigation and communications, the inReach was also being used to geotag the images collected as the documentation of the food fishery was completed.

With the trip’s images in hand and a tight schedule to maintain, two days and 700 kilometers of icy, frozen roads later, we rolled into the snow-covered Tahltan village of Iskut. It was March 14, and COVID-19 was beginning to seriously make its presence known in Canada. By that point, there were 257 active cases across the country, including 73 in British Columbia.

At an elevation of 848 meters, with a clear star-filled sky overnight, the temperature slid to minus 20 degrees Celsius. In the sharp, cold darkness of the winter morning, the Jeep started, and, immediately, cold, thick engine oil began streaming down the frozen engine block. It was flooding out of the engine’s oil cooler and pooling on the hard-packed snow beneath it at an alarming rate. The oil cooler’s seals had failed, and the frigid weather had exacerbated the situation. The Jeep was packed with a full range of emergency supplies, and with an additional 3 liters of synthetic engine oil on hand, the decision was made to continue to run the engine and replenish the leaking oil as it came up to operating temperate, with the hope that the engine components would expand and reseal as they warmed. Assuming the seals held, this would enable the Jeep to make the 500-kilometer journey to Terrace, the nearest service center, for repairs. Fortunately, luck was on our side, and soon the flow diminished to a trickle, and after about 15 minutes ceased entirely.

The decision to make a run for emergency repairs at Terrace, through one of the most isolated parts of British Columbia in the dead of winter, was only possible because of the capability and confidence the Overlander and inReach units provided. We were able to track their fuel and oil consumption relative to the infrequent fuel stops along the isolated route with the Overlander, with the certainty that we could always readily summon assistance in a worst-case scenario using the inReach.

After safely arriving in Terrace, engine parts were flown in and the Jeep successfully repaired. However, at this point, the country was rapidly shutting down around us as it was gripped in the throes of COVID-19. Travel bans were being imposed, and the federal, provincial, territorial and indigenous governments were all advising travelers to go home and stay there. After such extensive planning, preparation and expense to undertake the winter expedition to the Arctic, the painful but necessary decision was made to protect the health and safety of Canadians and return to Vancouver Island.

The trip home was surreal; empty highways, closed restaurants and vacant gas stations greeted us as we got ever closer to our destination.

Once home, the consensus between us and our partner organizations was that the unfinished project remains a priority. A follow-up expedition to the Nass Valley to work with the Nisga’a, in collaboration with the Royal British Columbia Museum, is being planned for next year, as is another winter foray by road to the Arctic Ocean in 2021, with inReach guiding the way.”

NOTICE: To access the Iridium satellite network for live tracking and messaging, including SOS capabilities, an active satellite subscription is required. Some jurisdictions regulate or prohibit the use of satellite communications devices. It is the responsibility of the user to know and follow all applicable laws in the jurisdictions where the device is intended to be used.